In ordinary English, “idealism” is contrasted with pragmatism. “Idealism” refers to the prioritizing of ideals. The meaning of idealism in philosophy is different. In philosophy, the meaning of “idealism” is the view that the physical universe arises from consciousness. Philosophical idealism is contrasted with realism. Realism posits that everything arises from a physical universe fundamental such as quantum particles, strings, or some other type of irreducible objects.

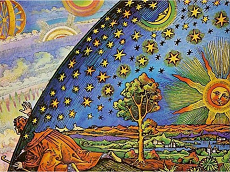

There are various branches of idealist thought. For example, one branch of idealism posits a single source of consciousness which is “dreaming” the physical universe. Just as the people and cars and houses in our dreams at night seem real to us, the physical universe seems real to us even though it is being dreamed. This is a key assumption of Buddhism. When we wake up in the morning, we say to ourselves, “Oh, it was just a dream.” When people wake up from the “illusion” of the physical universe, Buddhists say that they have woken up and are now Enlightened.

Idealism is not uniquely an assumption of Buddhism and other Eastern religions. Western philosophers, for example, the ancient Greek philospher, Plato (428/427 to 348/347 BC); the British philosopher, George Berkeley (1685-1753); and the German philosopher, Immanuel Kant (1724-1804); all espoused varieties of idealism.

Idealism and the Early Development of Quantum Physics

The development of quantum physics in the 1920’s and 1930’s inspired renewed interest in idealism among some scientists. Sir Arthur Eddington (1882-1944) was among these. Eddington was a leading astronomer of the early 20th Century. His observations of stars during a solar eclipse confirmed Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity. He wrote in his book The Nature of the Physical World that “The stuff of the world is mind-stuff”:

“The mind-stuff of the world is, of course, something more general than our individual conscious minds…. It is necessary to keep reminding ourselves that all knowledge of our environment from which the world of physics is constructed, has entered in the form of messages transmitted along the nerves to the seat of consciousness….It is difficult for the matter-of-fact physicist to accept the view that the substratum of everything is of mental character. But no one can deny that mind is the first and most direct thing in our experience, and all else is remote inference.”

The 20th-century British scientist Sir James Jeans wrote that “the Universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine”

Ian Barbour in his book Issues in Science and Religion (1966), p. 133, cites Arthur Eddington’s The Nature of the Physical World (1928) for a text that argues The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principles provides a scientific basis for “the defense of the idea of human freedom” and his Science and the Unseen World (1929) for support of philosophical idealism “the thesis that reality is basically mental”.

Sir James Jeans wrote: “The stream of knowledge is heading towards a non-mechanical reality; the Universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine. Mind no longer appears to be an accidental intruder into the realm of matter… we ought rather hail it as the creator and governor of the realm of matter.”[84]

Jeans, in an interview published in The Observer (London), when asked the question: “Do you believe that life on this planet is the result of some sort of accident, or do you believe that it is a part of some great scheme?” replied:

I incline to the idealistic theory that consciousness is fundamental, and that the material universe is derivative from consciousness, not consciousness from the material universe… In general the universe seems to me to be nearer to a great thought than to a great machine. It may well be, it seems to me, that each individual consciousness ought to be compared to a brain-cell in a universal mind.

Addressing the British Association in 1934, Jeans said:

What remains is in any case very different from the full-blooded matter and the forbidding materialism of the Victorian scientist. His objective and material universe is proved to consist of little more than constructs of our own minds. To this extent, then, modern physics has moved in the direction of philosophic idealism. Mind and matter, if not proved to be of similar nature, are at least found to be ingredients of one single system. There is no longer room for the kind of dualism which has haunted philosophy since the days of Descartes.[85]

Today, there is renewed interest in idealism among philosophers and scientists. For example, Donald Hoffman, a cognitive scientist, and Bernardo Kastrup, a philosopher and computer scientist, have published books and articles espousing versions of idealism. These publications address the key questions raised by idealism:

- How does it happen that we are all having the same “dream”?

- Why is the “dream” so lawful?

- If the physical universe arises from consciousness, why can’t we change what happens in the physical universe by our own volition?

Scientific Realism

However, mainstream science since at least the time of Isaac Newton (1643-1727) and into current times assumes realism. Specifically, relies on a version of realism called “scientific realism.” Scientific realism assumes that a form of physical energy, possibly strings or quantum fields or…, is fundamental and everything else arises from this fundamental physical thing. And regarding consciousness, it’s part of “everything else” that arises from the physical fundamental thing. Usually the assumption is that consciousness arises, in an unknown manner, from the physical brain.