In quantum mechanics, the term “observer” is used in a specialized manner. It has a meaning quite different from that of the regular English word.

In quantum mechanics, an observer is anything that detects a quantum particle. Physicists say that an observer measures the properties of a quantum particle. Observation is also called “measurement.” Understanding the role of the observer depends upon understanding the special role of measurement in quantum mechanics. If you’re not familiar with this role, please see the article on measurement.

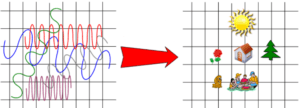

Modification of David Chalmers and Kelvin McQueen, “Consciousness and the Collapse of the Wave Function” http://consc.net/slides/collapse.pdf]

The mathematical description of the wave tells us only about probabilities that we will find it in particle form in specific positions. But the quantum wave specifies no definite position. Upon hitting Filipe’s retina, the photon takes on a position. At that moment, it becomes a localized particle. The photon is absorbed by a specific electron in the retina and gives the electron additional energy. The energized electron creates an electrical impulse in Filipe’s brain and he has the experience of seeing. This, of course, is an oversimplified description of sight which leaves out quite a bit.

Observation and Information Theory

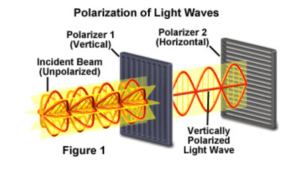

Observation requires a transfer of energy between the observer and that which is observed. In our example, the photon from the sun gives energy to the electron in Felipe’s retina. One way to think about the term “observer” is that the interaction is called observation because it is the moment at which the photon becomes observable. At this moment, it has created a physical change in our universe. In this way, it is observed and recorded in the history of our universe. An information theorist would say that the photon has created information.

Must the observer be conscious?

The use of the term “observer” in quantum physics can be confusing. It seems to imply it’s a human being or maybe a particularly astute cat. In the 1920’s and 30’s, pioneering quantum physicists like John Von Neumann and Eugene Wigner postulated that human consciousness collapses the wave function. But, today, most physicists reject this idea.

Consciousness, however, may play another role in quantum mechanics. Recently, physicists and philosophers have proposed that our universe is a simulation. This is the idea that we’re living in a virtual reality very much like characters in a video game. One version of this idea, proposed by philosopher, Nick Bostrom, is that we’re living in a computer simulation created by an advanced race of beings.

Another version of the simulation hypothesis, however, harkens back to an ancient Buddhist idea: Our physical universe is dream, a highly-lawful dream. (See, for example, the interviews and writings of cognitive psychologist, Donald Hoffman and of quantum physicist, Henry Stapp). In an updated version of the Buddhist idea, life is like a video game, a virtual reality. It runs in accordance with mathematical equations and is possibly fed data by the players of the game. In this view, the equations are fleshed out into an experiential reality by our consciousness. The virtual reality runs like a movie, a highly organized dream, in the mind. Possibly, it’s running in one all-encompassing mind that all of us players are plugged into.

How does this version of the simulation hypothesis relate to quantum mechanics? Quantum mechanics is a set of equations which underlies physical reality. How do we get from equations to the physical reality that we experience? Stephen Hawking asked the question this way: “What is it that breathes fire into the equations...?” One possible answer is consciousness.

Not all interactions result in observation.

Not all interactions represent an observation and the creation of information. The observer must exchange energy with a particle for an observation to occur. Here’s an example of an interaction where there is no exchange of energy: when particles entangle with each other. The particles do not act as observers for each other. Instead, they retain their wavy quantum state. Later, however, if one of the particles is observed, it adopts properties in physical reality.

Any physical object can be an observer.

Of course, the observer needn’t be a particle in a detector screen or even the retina of a human eye. Any particle—any atom, subatomic particle, or molecule—can act as an observer. So long as the observer interacts energetically with a particle, the particle loses its wavy quantum state and transforms into a particle. This is an observation (measurement).